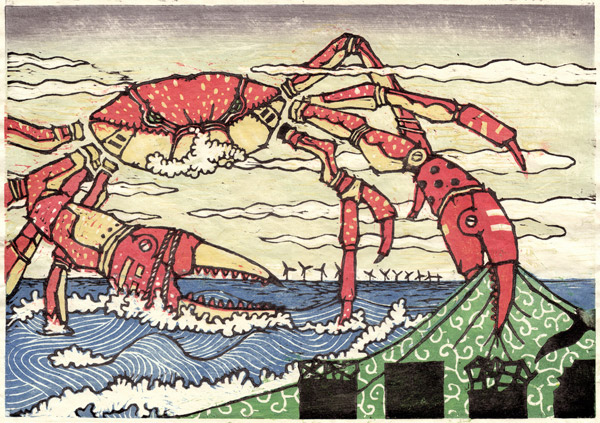

Ok - det story first. The nine-year old boy Ren is full of resentment against the world after his mother's death and runs away from home to live as a street kid in Shibuya. Trying to escape the police, he loses his way and ends up in the supernatural world of the bakemono (monsterlike beings portrayed as mixtures of animals and humans) that exists in parallel with the normal, human world. In contrast to grey, murky Tokyo, the bakemono world is a sunny and magnificently beautiful pre-modern town. Significantly, while Ren is isolated and surrounded by anonymous masses in Tokyo, in the bakemono world he is constantly talked to and talking back. The bakemono world is a world of communication and human contact.

Ren becomes the disciple of Kumatetsu, a bearlike bakemono who is strong but uncouth and short-tempered. Ren - who is now known as Kyûta - settles down in Kumatetsu's untidy house where they spend their time quarrelling and scolding each other. "Grasp you inner sword!" (Mune no naka no ken o nigirunda), Kumatetsu shouts at the bewildered Kyûta, who doesn't know what to make of this strange injunction and simply shouts back at his teacher. Despite Kumatetsu's inability to provide intelligible guidance, Kyûta grows into a skilled fencer by imitating him. Meanwhile, two friends - the pig-like Buddhist monk Hyakushûbô and the monkey-like Tatara - help educate the boy. As Kumatetsu becomes a father-figure for Kyûta, he himself develops a sense of responsibility, becomes a more skilled teacher and acquires more disicples. When Tatara admiringly talks about how skilled Kyûta has become as a swordsman, Hyakushûbô says that Kumatetsu has grown too: "It's hard to tell who is the master and who is the disciple".

As Kyûta becomes a teenager, the film's atmosphere changes, much of the playfulness disappears and the stage shifts back to Shibuya. Kyûta finds his way back to the human world, where he meets a kind girl, Kaede, who teaches him to read. While discussing Moby Dick she tells him that the whale is not evil in itself - the evil is just the projection of Ahab's own hatred. Kaede is a very proper girl - a trait shown when she asks a group of noisy teenagers to leave the library (later Kyûta has to help her since the teenagers wait outside the library to take revenge on her). Kyûta also manages to find his dad. He decides to leave the bakemono world, but in a fit of rage he runs away from his dad and in the night he meets a terrifying apparation with a black hole in its chest. He realizes that it is himself and that the hole is the inner "darkness" which the bakemono have told him that all humans develop. When he finds Kaede, she manages to calm him by giving him a red ribbon which she says was a bookmark from a book that she loved as a child.

Meanwhile, the time has come for Kumatetsu to face his rival, the equally strong, boarlike bakemono Iôzen. The fight takes place in full public view in a gigantic arena and will determine who will be the next leader (sôshi) of the bakemono. The present leader, a rabbit-like bakemono, has decided to retire and become a god or kami. In contrast to the Kumatetsu, Iôzen is a wellbred, aristocratic figure who is popular with the crowd, has many disciples and lives in an elegant residence surrounded by a bamboo forest. Kumatetsu is on the verge of losing when Kyûta comes back. His spirits raised, Kumatetsu defeats his opponent but is then pierced from behind by a flying sword that is controlled by Iôzen's human son Ichirôhiko – who until now has concealed his humanity but who like all humans has an inner darkness in the shape of a terrifying black hole - and only barely survives. Kyûta and Ichirôhiko meet for a final battle in Shibuya. Ichirôhiko transforms himself into a seemingly invincible flying whale, but Kyûta defeats him with the help of Kumatetsu, who decides to sacrifice himself in order to become an "inner sword" that can fill up the hole in Kyûta's chest. Instead of killing his enemy, Kyûta gives him the red ribbon that he himself had gotten from Kaede. The end is happy – Kyûta is celebrated by the bakemono, gets his girlfriend, reconciles himself with his dad and Kaede persuades him to start studying at a university. He quits fencing but continues to carry his "inner sword" for the rest of his life.

To me, this ending left a bad aftertaste and even a kind of claustrophic feeling. Firstly, part of this feeling comes from the use of "Shibuya" as a metonym for the human world, or at least for the human world as experienced by Japanese youth. Here is certainly the place to ask: who is excluded by the use of such metonyms? Shibuya, for those who don't know, is a popular shopping and entertainment district in Tokyo which is a centre for youth fashion and culture. Unlike, say, neighboring Shinjuku, it is a place that produces the impression of a world divorced from work and from problems related to aging. It's a place above all for young people with money to spend.

But if there is nothing wrong with "Shibuya", what then is the need for a parallel world? After all, the function of such worlds in fiction has usually been to address some deficiency in the real world. What is it that the bakemono world offers Kyûta that cannot be found in "Shibuya"? The answer is: an object with which to fill up his "inner darkness". When Kumatetsu turns himself into an "inner sword" he becomes such an object - an introject in the form of a father figure. Is a "father" then what is lacking in "Shibuya"? The preoccupation with fathers in the film is rather startling considering that, biologically speaking, it is not the father but the mother that Kyûta is missing. In present society, the film seems to say, "fathers" are missing despite the presence of biological fathers, and that's why Kyûta needs to travel to the parallel world to find a non-biological father.

Why is it a father - Kumatetsu - that Kyûta seems to need and why not a mother? A look at the role of women in the film shows that it is caught up in traditional gender stereotypes: fighting is the business of men, while women are associated with literature, healing and the power of love. Kaede is not an unimportant figure - she is the one who provides Kyûta with an ideal of to strive for in life and steers him back into mainstream society - but she depends on Kyûta for protection both against bullying teenagers and against the rampaging Ichirôhiko. It is also significant that she is part of the human world, not the bakemono world, which is overwhelmingly masculine. What the latter world provides is a place where boys can grow into "men" in an unabashedly traditional sense, a place where they can be real fighting men. Such places, the film seems to say, are missing in today's mainstream Japanese society. At this point, the suspicion arises that the bakemono world may be a code for the criminal underworld. That would explain a lot of things - not just the prominence of violence and katanas, but also the central role of masculinity.

At the same time, the film does not one-sidedly affirm this masculine, martial world. Instead, it operates with an idea of a reconciliation between the masculine and the feminine. This reconciliation comes about through Kyûtas's successful socialization, which enables him to unite the best of the bakemono world and the human world - the fighting spirit of Kumatetsu and the gentleness and orderliness of Kaede. We can note in passing that orderliness plays an important structuring role in the film. While there is a good, attractive disorderliness - symbolized by Kumatetsu - this disorderliness has to be overcome (an act symbolized by Kyûta's cleaning up of Kumatetsu's untidy house and Kumatetsu's own development into a responsible father figure). Even worse is the purely evil disorderliness symbolized by the noisy teenagers in the library and their bullying of Kaede - a disorderliness that, unlike Kumatetsu's, is unredeemable and must be subdued by force. On the other hand, there are also "good" and "bad" forms of orderliness. While Kaede stands for the good variety, Iôzen stands for the bad - an orderliness that looks splendid from the outside but that coxists with arrogance. What the film does is to unite two "goods" (Kumatetsu and Kaede) while rejecting two "bads" (the teenagers and Iôzen). The union of the goods (the "complex term" to speak with Greimas) is symbolized by the "inner sword" which enables Kyûta to preserve his fighting spirit even as he adapts to mainstream life, while the union of the bads is personified in Ichirôhiko who wrecks havoc with the world out of resentment at seeing his admired father fall victim to the plebeian Kumatetsu.

Let me now return to the setting. There are works of fiction in which the idea of a parallel world is deployed above all for escapist purposes. That is not necessarily bad, since in such works there is at least an awareness that the real world which one is escaping is not perfect. This film is not an escapist work. It recognizes that problems exist in real society - such as the lack of father figues - and attempts to portray how a possible resolution or reconciliation might look. This, however, is where the feelings of claustrophia set in, because the reconciliation is too premature to have persuasive power. It happens on a purely individual level, through Kyûta's coming of age, without the rest of society having to change one iota. The film seems to want to say: I don't want to change society, only to help you become harmonious parts of it - and my solution is to offer you a sojourn to a world of human contact, where you can develop with a father figure as a model, try out your powers under the surveillance of benevolent adults and establishes ties of friendship and love that allow you to realize the importance to responsibility. It's a little bit like an NGO that seeks only to help delinquent youngsters to "return to society" (shakai fukki, as it is known in Japanese) without breathing a word of criticism against the society it returns them to.

This subservience to mainstream society is what makes the film so different from, say, Miyazaki Hayao's Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi), which similarly portrays a young child who finds her way into a supernatural parallel world in which she has to go through a number of trials in order to return to the human world. In Miyazaki's film there is nothing that suggests that Chihiro's adventures in the other world will make her a harmonious part of mainstream society. Quite to the contrary, her stay in the other world opens up her eyes to wrongs performed by humans, such as pollution and the destruction of rivers. There is even a suggestion of a critique of capitalism in the film's portrayal of Kaonashi, who seems to believe that money can make up for the absence of friends, who starts to devour people, and whose appetite only grows the more he devours - a metaphor for endless capital accumulation. Chihiro's adventures in the other world seem almost like a training for the struggles she will have to fight in the future to rectify the human world. In Spirited Away, then, the parallel world is deployed as a device for groping for ways to overcome the real social ills without the film portraying the reconciliation as already achieved.

|

| Capitalism? |

The harmony between "Shibuya" and the bakemono world also suggests a nationalistic idea, namely that despite its modernization, Japan is still a "land of the gods" - that beneath the everyday, grey surface, it is still a glorious and colourful land of supernatural beings who stroll about with katana. According to this idea, Japan has not lost its national essence, which lives on in the hearts of young Japanese, just like Kumatetsu lives on in Kyûta's heart in the shape of an "inner sword". As Spirited Away shows, the idea of a "land of the gods" can be given an inflection that turns it into a criticism of the state and of capitalism. This can also be seen in historical phenomena such as the Ee ja nai ka-movement or the idea of a rectification of the world (yonaoshi) that informed many of Japan's millennarian movements. This, however, should not blind us to how often the idea of the "land of the gods" has been mobilized to prop up the legitimacy of the state, the emperor or of mainstream society. Dear Hosoda Mamoru, couldn't you please have moved away a little further from that latter legacy?